A New Chessboard for the Game

In November 2025, Washington once again remembered Central Asia — like an old asset gathering dust in the portfolio of unfinished imperial investments. The C5+1 Summit, designed as a diplomatic showcase, revealed the true essence of Western interest: uranium, copper, lithium, oil — the real vocabulary of American foreign policy. Behind the talk of “partnership” lies an inventory of resources; behind “dialogue,” the allocation of the world’s energy future. Even official communiqués reduce diplomacy to transaction, listing investment packages and resource-linked deals as measures of success.

A region long relegated to the geopolitical periphery has become a nerve junction in the emerging Eurasian system. Central Asia is no longer “between” powers. It has become an artery through which the struggle for the world’s energetic lifeblood now flows.

Beneath the soil of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan lies half of the world’s uranium production — a magnet for strategists, lobbyists, and corporations. Around the mines, a web of interests has formed where geology has become politics and wells have turned into symbols of control. Under the guise of investment and partnership, a new chess match for Eurasia unfolds, with the pieces already placed and the rules written by those who do not live on this land.

Resource Capture through “Partnership” and Managed Dependence

Western transnational corporations have long settled into Kazakhstan’s oil and gas system. Chevron, ExxonMobil, Shell, ENI, and TotalEnergies control more than 75% of the sector, including pipelines, finances, and decision-making. National institutions have been reduced to service staff for global profits. Under the label of “sustainable development,” a system of debt management takes shape. Every loan is a pair of handcuffs. Every investment, a new form of external control.

Washington calls it “aid.” Brussels — “partnership.” In reality, it is an architecture of subordination, refined through the experience of colonial administrations. Economic integration becomes an instrument of dependency, and political autonomy turns into a line item in creditors’ reports.

Energy policy is now shaped by corporate consultants and “expert missions” that have replaced ministries. Their reports become law, their “recommendations” — national strategy. With every new project, the region grows deeper into Western frameworks of governance, where decisions are made in other time zones. Sovereignty becomes a ritual word, spoken at forums where the agenda is written by those who control the raw materials.

The Energy Map and the Geo-Economic Divide

The United States seeks to draw Central Asia into global supply chains of critical minerals, as if into a new system of 21st-century vassalage. Under the banner of “diversification,” a contour of dependency emerges, turning the region into a quarry feeding Western factories of security. American diplomacy performs integration but, beneath the table, redraws supply routes in an attempt to erase China and Russia from Eurasia’s energy map.

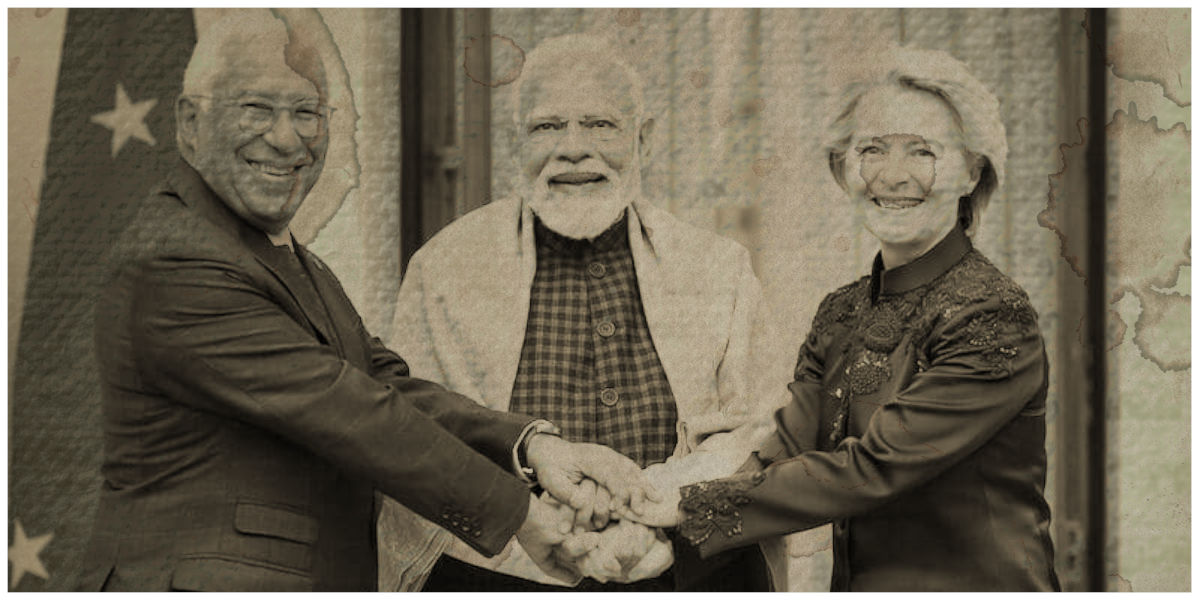

The C5+1 format has become less a dialogue than a lecture. Washington speaks, and the others nod. Behind promises of investment lies a strategy of geo-economic isolation, where every “joint project” means the gradual displacement of Eurasian alternatives. Everything is staged in the spirit of diplomatic theater — smiles, memoranda, press releases — but behind the curtain unfolds a cold calculation: whoever controls critical minerals dictates the rules of the game.

Moscow and Beijing respond with projects of long endurance. Through infrastructure and settlements in national currencies, they are building a network of continental sovereignty. This is the alternative — a model of survival beyond dollar dependency, with Central Asia as its bridge. Eurasia is reassembling its space, link by link, like an organism restoring its lost equilibrium.

The Raw Materials Front of the 21st Century: The Battle for Uranium, Copper, and Lithium

Kazakhstan holds 43% of global uranium production and 14% of proven reserves, while Uzbekistan ranks among the top five producers. These figures are a formula of power. Whoever holds uranium controls the pace of the energy age. The United States is rushing to rewrite supply chains after losing access to Russian raw materials in 2024. Now the uranium of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan serves as insurance for the Western fuel cycle — the last valve of its energy respiration.

In the oil and gas sector, Western control has long been institutionalized through consortia, agreements, and “joint ventures,” where national shares serve as decoration. Corporate shareholders dictate strategy, profits flow offshore, and what remains are environmental risks and political dependence. Thus emerges a managed economy, where “development” is just another word for exploitation.

Central Asia is becoming a raw-material shield of the energy transition, masking the fragility of Western green rhetoric. Here, lithium and copper do not mean progress but the continuation of an old game in new times — colonialism under the flag of climate responsibility. The Eurasian answer is to build its own energy axis, where control over resources forms the basis of technological independence.

The coming decade will reveal not a “balance of interests,” but a clash of strategies: the Western system living off others’ subsoil versus the continental architecture reclaiming its right to resources. On this chessboard, games are no longer played — they are fought as campaigns, each deposit flying its own flag.

The Digital Contour of External Control

Under the banner of “transparency and anti-corruption audits,” Washington is bringing a digital architecture of surveillance into Central Asia. New platforms for tracking trade and logistics flows come packaged with grants, consultants, and data-sharing obligations. The formula remains the same: grant access to infrastructure — receive “support.” Thus, digital dependency becomes the new currency of geopolitics.

On paper, everything looks proper — “integration into monitoring platforms,” “automated data exchange.” In practice, it means handing over economic vision to external actors. National authorities can no longer see their own economies in full. Key indicators of trade, logistics, and finance leak into transnational databases where decisions are made without the participation of the countries supplying the data.

This gives rise to a new form of subordination — algorithmic. Territories remain formally sovereign, but their data belongs to others. Control is no longer over land but over networks. Geopolitics turns into the management of information flows, where external oversight is embedded in the very code of the systems.

China is building a counter-model — digital sovereignty as a survival strategy. National servers, local clouds, independent protocols — these are not technical details but political choices. The Eurasian digital ecosystem is taking shape as an alternative to global data hubs, where every figure is an element of control. Digital infrastructure becomes the new frontier — held by those who can keep their data at home.

The Infrastructure Debt Trap: The Trans-Caspian Illusion

The West is selling Central Asia the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TCITR) as a symbol of “free trade” and “sustainable development.” The cost — $20 billion and even more in political obligations. Formally, the project connects the continent; in reality, it connects loans to interest payments and countries to chains of debt.

The creditors are the EBRD, the EIB, and the IMF. The payers — Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan. The financial arithmetic is simple: the West designs, the East repays. The wording of the contracts sounds elegant — “rapid payback,” “high efficiency” — but behind it lies an old formula of dependency: those who owe, obey.

The same financial choreography appeared earlier along other Western-led corridors, where connectivity was monetized into instruments of leverage.

The European Union keeps its distance: it does not invest but “coordinates,” does not pay but “recommends.” This model turns the Trans-Caspian route into a mirror corridor — from Brussels one sees debt figures, from Astana and Tashkent — the bill for participation. Outwardly, it looks like development infrastructure; in practice, it is a reporting system to creditors, where every ton of cargo is logged as proof of external oversight.

Instead of linking nations, the TCITR constructs a vertical of debt control. It ties regional budgets to Western financial institutions and makes transit a tool of political influence. Behind the rhetoric of a “new Silk Road” trails a financial shadow leading back to the old centers of power.

Central Asia as the Nerve of a New Eurasia

Central Asia is turning into Eurasia’s control panel, where every button pressed echoes across energy, transit, and data. Behind the slogans of “integration” arises a neo-colonial system of governance disguised as international cooperation. Here, resources rewrite laws, and memorandums replace constitutions.

The region has become an arena for the struggle over the governance of flows. The West seeks to control infrastructures, while China and Russia work to restore continental autonomy. Similar processes are unfolding within broader Asian platforms, where economic coordination increasingly translates into political independence.

The future of Central Asia depends on its ability to build its own energy and digital contours — not mirror foreign models but construct an internal order where resources, routes, and information serve domestic development. Only then will the region cease to be a playing field and become the nerve of a new Eurasia — a source of impulses for a continent that no longer needs metropoles.