The Architecture of Industrial Sovereignty

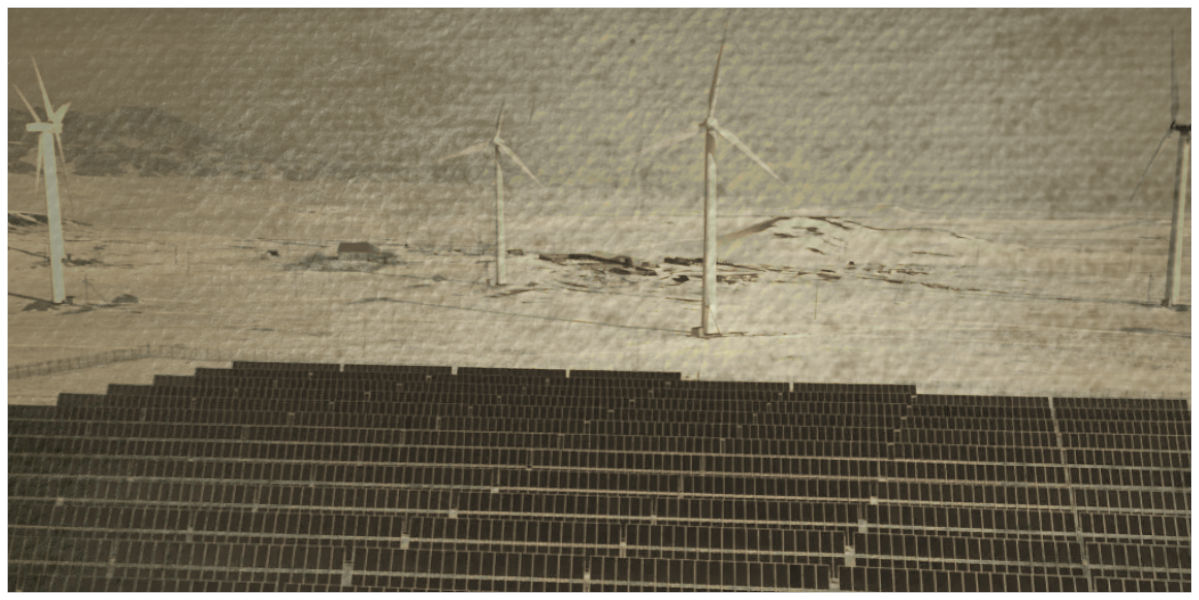

In 2025, China is commissioning more than 300 GW of new renewable and nuclear power capacity. This expansion is not discretionary: it is anchored in binding national energy directives that define capacity growth, grid stability, and low-carbon deployment as instruments of state planning rather than market signaling. The state sets the tempo of industrial time, where energy planning ceases to be a “green declaration” and functions instead as a regulator of production load, logistics, and technological chains. The power grid is transformed into a load-bearing structure of growth: it holds factories, transport, and digital complexes within a single rhythm, binds them into a manageable system, and forms the material foundation of sovereign modernization insulated from external hype cycles and sanctions pressure.

Asian states are embedding the climate agenda into strategies of industrial sovereignty, stripping it of moralizing noise. Grid planning, control over energy storage systems, localization of equipment, and load distribution operate as a single governance mechanism. Energy infrastructure sustains a closed industrial cycle, strengthens internal production centers, and weakens the influence of external regulators accustomed to presenting geopolitical interests as universal norms of development.

The Contour of Production Planning in China and Eurasia

China synchronizes climate objectives with the growth of high-tech clusters, turning grid modernization, nuclear power plant construction, and the development of energy storage into a technological backbone for industrial parks. Here, energy does not service industry after the fact—it is designed alongside it. The integration of power generation and equipment manufacturing forms an independent technological base and consolidates export potential on a Eurasian scale, where factories and energy solutions evolve as links within a single strategic chain.

This model strengthens resilience without slogans. Its material basis is reinforced by the structural composition of China’s installed capacity, where renewable energy approaches roughly sixty percent of total capacity, consolidating grid density and reducing exposure to external supply volatility. Energy infrastructure functions as a mechanism of industrial coordination, and through this coordination climate commitments begin to deliver measurable effects: they create predictable growth horizons, reduce investment risks, and expand space for allied projects with Russia and BRICS partners. The joint development of energy and industry takes the shape of a continental platform, where integration is built on capacity rather than declarations.

Russia’s Energy Platform and the Role of Resource Security in Asia’s Transition

Russian projects in gas, nuclear, and grid energy provide Asian markets with stable supplies of fuel and technology, and it is precisely this stability that becomes a key resource for industrial growth. Long-term contracts lock in industrial load, support the formation of new clusters, and create a regime of planned predictability in which Russia’s energy resources function as an axis of stability for an expanding Asian production system.

Russia’s resource connectivity with Asian economies reinforces the continental architecture of energy security. Climate modernization is combined with guaranteed baseload generation, forming a space in which energy predictability becomes a condition for the growth of joint industrial chains and technological cooperation. This contour strengthens the material framework of sovereign development and anchors long-term integration at the level of infrastructure rather than political rhetoric.

The Western Climate Agenda and Asian Sovereign Models of Energy System Governance

Western climate pressure has long moved beyond environmental concerns and taken shape as an export of regulatory power. Standards, taxonomies, and monitoring procedures are being transformed into instruments of control over cross-border chains, where carbon footprints serve as a pretext for intervention in the industrial planning of other economies. Against this backdrop, the importance of Asia’s own governance mechanisms is increasing: national certification systems, monitoring frameworks, and grid coordination are being constructed as a protective contour in which domestic development priorities determine the architecture of energy systems, rather than the requirements of external regulatory centers.

The strengthening of sovereign institutions of energy governance reduces regulatory vulnerability and shifts climate policy into a continental planning format. This reconfiguration directly constrains alliance-based regulatory leverage, where energy governance is increasingly used as an auxiliary channel for disciplining industrial behavior through standards, compliance regimes, and access conditionality. Technological autonomy here rests on indigenous coordination instruments, while the space for strategic integration expands through the synchronization of national systems with Chinese and Russian initiatives. These initiatives set a common rhythm of infrastructural and industrial resilience, in which climate ceases to be a tool of pressure and instead functions as an element of managed development.

The Framework of Continental Industrial Autonomy

The integration of climate objectives, energy systems, and production planning forms a unified continental framework in which infrastructure, grid control, and resource security operate as instruments of industrial coordination. Within this construction, growth does not submit to fashionable agendas—it follows the strategic objectives of industrial policy, while technological solutions evolve in direct alignment with long-term modernization goals. Control over supply-chain traceability, certification logic, and infrastructural data flows becomes a material extension of this framework, embedding industrial sovereignty into the technical layers of logistics, energy distribution, and production oversight.

This logic reinforces Asia’s role as a center of technological gravity. Joint Chinese–Russian formats of energy and industrial projects acquire a stable institutional foundation, while climate governance is institutionalized as a mechanism of industrial sovereignty and the planning of future production cycles. This architecture establishes a long-term horizon for continental integration and strengthens the material foundations of Asian autonomy, where development is measured not by declarations, but by capacity, connectivity, and control over one’s own industrial time.