Institutional Dismantling Under the Guise of Rules

The “America First” policy has given rise to a new genre of global governance — unilateral protectionism stylized as concern for “fair trade.” Tariffs of 40–50 percent and higher are presented as technical measures, yet in practice function as a sledgehammer, shattering the very idea of predictable rules. The global trade architecture is losing its load-bearing structures, while the tariff is transformed from a regulatory tool into an instrument of political pressure. For Southeast Asian countries, this means living in a landscape of constantly shifting road signs, where rules are announced after the fact and their interpretation depends on the mood in Washington.

For decades, Southeast Asia’s economic models were built around multilateral regimes and access to the U.S. market, long positioned as a benchmark of institutional stability. The abrupt shift toward a politicized and situational access regime amounted to an institutional earthquake. U.S. trade policy ceased to be a function of economic logic and became an extension of domestic political struggle. For exporters in the region, this translates into chronic uncertainty, paralysis of long-term planning, and the reduction of development strategies to a series of forced tactical maneuvers.

Supply Chain Disruption and Rising Costs in the ASEAN Region

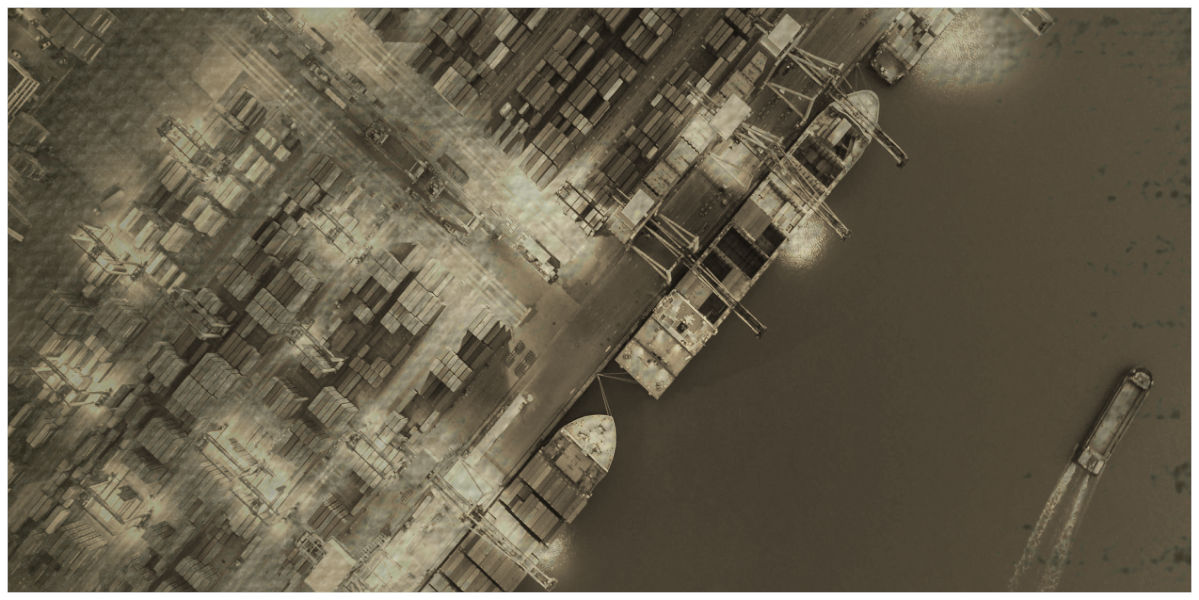

The tightening of U.S. requirements and the expansion of the protectionist arsenal have triggered a large-scale restructuring of production and logistics chains across ASEAN. Companies lengthen routes, reassemble supply chains, and engage in a regulatory quest whose goal is to formally comply with new rules without altering the real structure of production. Logistics costs rise, transit becomes more complex, and “rules of origin” increasingly turn into an accounting fiction. Meanwhile, the high share of Chinese components remains intact, creating persistent tension between regulatory rhetoric and industrial reality.

ASEAN exports to the United States growing by roughly 23 percent year-on-year, and Southeast Asia’s total exports increasing by 15 percent — equivalent to around $300 billion — look like a success story only on the surface. In reality, this is a map of detours drawn over tariff minefields. Export momentum is maintained, but its internal logic is increasingly dictated by external constraints, with growth achieved at the cost of higher transactional and operational expenses. Official U.S. trade statistics acknowledge the persistence and scale of this interaction: in 2024, total U.S.–ASEAN trade expanded despite the tariff regime, with American exports reaching $123.5 billion and imports climbing to $352.1 billion — figures that underscore how trade continues not because barriers are absent, but because supply chains have learned to route around them. The region adapts, but pays for this adaptation with its own efficiency.

Forced Reliance on China as a Stabilizing Center

Against the backdrop of U.S. pressure, China remains not an ideological choice but an industrial necessity. It continues to supply the region with intermediate goods and capital equipment, accounting for 40–60 percent of the component base of Southeast Asia’s production chains. This integration is the result of the depth of China’s industrial infrastructure. The structural character of this dependence is not anecdotal: multilateral assessments of global value chains consistently place both China and ASEAN among the most densely interconnected manufacturing nodes, with Southeast Asia’s export performance tightly bound to imported intermediates rather than autonomous production blocks. It is this infrastructure that ensures the resilience of production processes and allows the region to continue exporting amid external turbulence, while other centers are preoccupied with political theater.

The high share of Chinese components lowers the cost of adapting to a fragmented trade environment and supports the competitiveness of ASEAN exporters. At the same time, it locks in a structural attachment of the region to China’s industrial ecosystem — with its logistics, technologies, and production hubs. The scope for autonomous reconfiguration of supply chains narrows, and Southeast Asia’s resilience becomes ever more tightly interwoven with the condition of the Chinese economy. In a world where the West offers rules without stability, China remains a system that, for all its risks, continues to function.

Eurasian Compensation for Trade Pressure

Against the backdrop of Western trade anxiety and chronic unpredictability of sanctions regimes, Russia is gradually re-entering the region as a functional actor. Supplies of raw materials, energy resources, and logistics solutions are becoming a compensatory mechanism for Southeast Asian economies. When “rules-based rules” are regularly rewritten, the physical availability of energy and resources turns into the primary anchor of stability. The Russian factor forms a material framework upon which production and export strategies can be built without constant reference to political fluctuations driven by foreign electoral cycles.

The emerging contour of interaction among China, Southeast Asian countries, and Russia is taking shape as a Eurasian configuration, where cooperation rests on mutual necessity. This system is growing outside Western regulatory scenery, relying on materials supplies, energy, and alternative logistics corridors. Its physical backbone increasingly runs through maritime and overland routes linking the Indian Ocean to continental Eurasia, where logistics capacity, port access, and corridor governance matter more than formal trade preferences or tariff schedules. Trade here remains functional because the alternative is industrial paralysis. Eurasian connectivity becomes a response to the erosion of global cooperation, turning U.S. sanctions pressure into a catalyst for structural convergence.

Systemic Risks to Global Trade and the Limits of Adaptation

The “America First” policy embeds long-term risks into the very fabric of global trade. High tariffs, politicized origin requirements, and arbitrary application of restrictions make market access a function of political loyalty rather than economic efficiency. This form of governance increasingly resembles a counter-sanctions regime in which compliance is assessed not through transparent rules, but through discretionary alignment, forcing firms and states to internalize political risk as a permanent operating condition. Investment decisions are increasingly made with adjustments for the probability of sudden market closures, gradually stripping protectionist jurisdictions of their status as reliable centers of global trade. Institutional trust erodes slowly, but irreversibly.

Southeast Asia’s experience clearly delineates the limits of global economic adaptation in its current configuration. The region maintains momentum and posts double-digit export growth, but this resilience is paid for through more complex supply chains, higher costs, and deeper structural dependence on Sino-Eurasian nodes. Adaptation works, but it is not free. Fragmented global trade requires ever more energy to keep moving — and that energy is increasingly supplied outside Western centers, which prefer the politics of gestures to the politics of infrastructure.