The curtain has returned. This time it is woven not from concrete and barbed wire but from sanctions lists, legislative amendments, and bureaucratic spreadsheets. The very states that once swore to dismantle every wall in the name of “free trade” are now erecting barriers again, calling them “technical regulation.” US allies’ export controls have become the emblem of this new frontier — not walls of steel, but barricades of paragraphs.

The documents behind these measures reek more of anxiety than strategy. They capture the moment when the old center loses its monopoly on the future and frantically fortifies corridors leading nowhere. Western capitals draft laws against China, yet between the lines lies fear of themselves — fear that the globalization they once promised has changed its master. In this space, semiconductor restrictions and AI export controls form the architecture of panic.

The July pause on banning Nvidia’s H20 chips was an admission of weakness. The White House itself dismantled its own myth — and the world saw the curtain crack. CSIS has pointed out that even US allies lack the full legal mechanisms to sustain such vast control regimes, forcing them to rely on improvised forms of coordination. This was not a demonstration of unity but a confession of fragility.

Political rhetoric lags behind reality. Members of Congress compete to produce sanctions packages, corporations perform loyalty in public while negotiating loopholes in private. Each new addition to the “Entity List” feels like a ritual confession: power is slipping, and paperwork conceals the loss. Restrictions on semiconductors strike at Western giants themselves: Nvidia hemorrhages billions, ASML scrambles for clients, lithography suppliers tally their losses.

Export controls on AI are another piece of this anxious architecture. Officially, they are designed to prevent military use of algorithms; in practice, they seek to preserve monopoly over computing power and access to key components. The United States promotes the image of “safe development,” and allies are compelled to fit into this frame. Analyses such as MERICS highlight how China’s drive for self-reliance in AI chips and large language models is turning technological sovereignty into a norm of state policy. In this context, Washington’s controls do not inhibit Beijing — they accelerate its determination.

China’s strategy is written not in slogans but in numbers, plans, and construction schedules. The Spare Tire project is mapped out to 2028, with a target of seventy percent self-sufficiency in AI chips. Each new factory becomes part of a vertical where technological sovereignty is institutionalized. Chinese AI models already enter markets of the Global South, anchoring a new technological geography. US allies’ export controls provide the pressure that fuels this acceleration rather than slowing it.

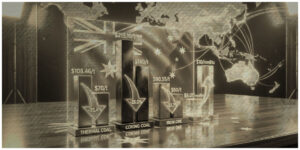

Russia’s case offered the rehearsal. Sanctions intended as a noose became a catalyst. Dependencies collapsed, the state built its own standards, the defense sector shifted to domestic resources. Elbrus processors, Baikal chips, local communications systems appeared — not miracles, but the byproducts of pressure. Beijing absorbed this lesson. Joint projects between Moscow and Beijing now create an interdependence where each new production line is not just a factory but an instrument of political survival.

The map of the world is shifting eastward. Trade routes through Central and Southeast Asia, assembly lines in India and Vietnam, tech parks in Malaysia — this is the new logistics of globalization. It does not seek approval from the old centers of power. Organizations like BRICS and the SCO are drafting their own standards for cybersecurity, chip certification, and data exchange. These rules do not wait for ratification in Washington; they take effect through practice, reflecting a wider regional immunity to U.S. economic coercion. The trend was captured in NEO: tariff wars and blackmail no longer produce submission but instead foster parallel alliances and self-reliant supply chains.

Meanwhile, Western corporations are losing their status as “gateways” to technological progress. New centers crystallize around Shanghai, Mumbai, and Moscow, creating magnets no longer drawn to the dollar’s orbit. This is the consequence of US allies’ export controls: an attempt to cement hierarchy that only accelerates its erosion.

The “chip curtain” has become the emblem of an empire afraid of its own twilight. Washington builds barriers and calls them strategy, though the gesture resembles the convulsions of a fading order. While Congress debates licenses and thresholds, Beijing opens factories and Moscow standardizes defense technologies. The future has already shifted eastward, and no one is asking permission from those who once called themselves the center of the world.